Hier, le 31 janvier, j’ai vécu une longue journée en explorant plusieurs musées de Johannesburg avec Abby Shine et deux de ses amies.

Hier, le 31 janvier, j’ai vécu une longue journée en explorant plusieurs musées de Johannesburg avec Abby Shine et deux de ses amies.

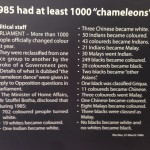

D’abord, nous sommes allés au Musée de l’apartheid dans le sud-ouest de la ville. Après avoir acheté nos billets, nous avons été étiquetés comme soit « blanc » ou « non blanc,» ce qui déciderait quelle porte nous traverserons pour rentrer dans le musée. Étant un

« blanc, » je suis entré par la porte désignée pourles « blancs » et j’y ai vu un collage d’anciennes cartes d’identité des personnes blanches datant de l’époque d’apartheid. À travers une barrière qui nous séparait des « non-blancs, » j’ai vu les cartes d’identité des personnes noires. Ces personnes devraient apporter leurs cartes en tout temps et devraient obéir à un couvre-feu tous les soirs. Parfois, des noirs allaient brûler leurs cartes en rébellion, mais ils étaient arrêtés immédiatement.

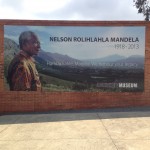

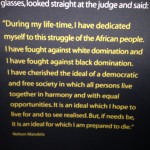

À l’intérieur du musée, j’ai appris beaucoup sur Nelson Mandela et ses efforts pour combattre l’apartheid. Le savais-tu qu’une professeure a donné le nom Nelson à Rolihlahla Mandela quand il s’est présenté à son école méthodiste à l’âge de sept

ans ? À la fin de la visite, nous avons eu la chance de placer un bâton coloré dans un genre de sculpture troué, ce qui symbolise qu’on suit dans les pas de Mandela !

Ensuite, nous avons traversé la rue pour visiter Gold Reef City, un parc d’attractions qui a comme theme une mine d’or, étant donné que Joburg a été établi lors d’une ruée vers l’or. Abby et ses amies sont allées sur une montagne russe pendant que je suis resté pour leur photographier. Nous sommes ensuite allés en ligne pour un deuxième manège. Lorsque c’était à notre tour d’embarquer, l’opérateur a laissé entrer trop de personnes puis il nous a demandé de retourner à l’avant de la file. Après que tout le monde a débarqué, il s’est tourné vers le ciel puis a proclamé que le manège était fermé à cause de la pluie. Il ne pleuvait même pas ! Bien sûr, 30 secondes plus tard, il commençait à pleuvoir des cordes. Comme nous étions en shorts et T-shirts, nous avons couru pour nos vies ! Nous nous sommes retrouvés dans un petit village qui ressemblait à un village des années 1880. On a décidé d’ensuite dîner afin de laisser passer la pluie, mais il nous semblait que tout le monde avait cette même idée aussi ! Les restaurants étaient blindés ! Nous étions assez chanceux de nous retrouver dix minutes plus tard en l’avant de la file à Mugg & Bean (genre de Starbucks sud-africain). Par exemple, une heure plus tard, la précipitation ne cessait toujours pas. On a décidé enfin d’appeler une voiture UBER pour nous amener à Soweto pour aller visiter la maison Mandela et le musée Hector Pietersen. Après l’appel, la pluie s’est arrêtée !

À Soweto, nous sommes allés visiter d’abord la maison Mandela, l’ancienne maison du leader. Celle-ci était décorée avec plusieurs objets soit qui lui appartenait ou qui lui décrivait tant comme personne : des prix, des sofas, le lit de ses enfants, des livres, des portraits, des articles de journaux, etc. Elle ressemblait plus à un musée que la maison de quelqu’un, ce qui est dommage, car j’aurais préféré si la maison n’était pas trop modifiée au fil du temps.

Nous avons conclu notre longue journée avec une visite au musée Hector Pietersen qui nous rappelle des émeutes de Soweto de 1976. Les émeutes de Soweto étaient la manifestation des élèves d’école jeunes qui ne voulaient plus prendre toutes leurs classes en Afrikaans, mais plutôt en Anglais, car c’était la langue qui leur servait la plus quand ils iraient travailler. L’armée s’est impliquée et a commencé à tirer sur les enfants et leur a tué. Un de ses enfants était Hector Pietersen qui n’avait que 13 ans. Mbuyisa Makhubo, un garçon de 18 ans, lui a pris dans ces bras et lui a apporté à un médecin qui lui a déclaré mort. Un photographe a capturé ce moment dans une photo iconique, ce qui explique pourquoi Hector est si célèbre. Par exemple, après ce jour, Mbuyisa Makhubo a fui le pays vers Botswana. Il a été vu la dernière fois en Nigerie en 1978. Très mystérieux, n’est-ce pas ? Là, il est cru qu’il soit actuellement dans une prison canadienne, mais des tests de vérification de l’ADN faits par le gouvernement sud-africain ne le confirmaient pas. Le musée, en général, était aussi triste qu’intéressant et donne bien sûr quelque chose à réfléchir.

En fin de compte, j’ai appris tellement sur l’apartheid dans une manière très personnelle que je n’aurais jamais avoir été capable d’en apprendre de chez moi au Canada. – Adam Vandenbussche ’17, Exchange Student at St Stithians College